Artificial Intelligence

In computer science, Artificial Intelligence (AI), sometimes called

machine

intelligence,

is intelligence

demonstrated by machines, in contrast to the natural intelligence displayed by humans. Leading AI

textbooks

define the field as the study of "intelligent agents": any device that perceives its environment and

takes

actions that maximize its chance of successfully achieving its goals. Colloquially, the term "artificial

intelligence" is often used to describe machines (or computers) that mimic "cognitive" functions that

humans

associate with the human mind, such as "learning" and "problem solving".

As machines become increasingly capable, tasks considered to require "intelligence" are often removed

from

the

definition of AI, a phenomenon known as the AI effect. A quip in Tesler's Theorem says "AI is whatever

hasn't

been done yet." For instance, optical character recognition is frequently excluded from things

considered to

be AI, having become a routine technology. Modern machine capabilities generally classified as AI

include

successfully understanding human speech, competing at the highest level in strategic game systems (such

as

chess and Go), autonomously operating cars, intelligent routing in content delivery networks, and

military

simulations.

Artificial intelligence was founded as an academic discipline in 1956, and in the years since has

experienced

several waves of optimism, followed by disappointment and the loss of funding (known as an "AI

winter"), followed by new approaches, success and renewed funding. For most of its history, AI

research has been divided into subfields that often fail to communicate with each other. These

sub-fields

are based on technical considerations, such as particular goals (e.g. "robotics" or "machine

learning"),the

use of particular tools ("logic" or artificial neural networks), or deep philosophical differences.

Subfields have also been based on social factors (particular institutions or the work of particular

researchers).

The traditional problems (or goals) of AI research include reasoning, knowledge representation,

planning,

learning, natural language processing, perception and the ability to move and manipulate objects.

General

intelligence is among the field's long-term goals. Approaches include statistical methods, computational

intelligence, and traditional symbolic AI. Many tools are used in AI, including versions of search and

mathematical optimization, artificial neural networks, and methods based on statistics, probability and

economics. The AI field draws upon computer science, information engineering, mathematics, psychology,

linguistics, philosophy, and many other fields.

The field was founded on the assumption that human intelligence "can be so precisely described that a

machine

can be made to simulate it". This raises philosophical arguments about the nature of the mind and the

ethics

of creating artificial beings endowed with human-like intelligence. These issues have been explored by

myth,

fiction and philosophy since antiquity. Some people also consider AI to be a danger to humanity if it

progresses unabated. Others believe that AI, unlike previous technological revolutions, will create a

risk

of mass unemployment.

In the twenty-first century, AI techniques have experienced a resurgence following concurrent advances

in

computer power, large amounts of data, and theoretical understanding; and AI techniques have become an

essential

part of the technology industry, helping to solve many challenging problems in computer science,

software

engineering and operations research.

Types of artificial intelligence

Arend Hintze, an assistant professor of integrative biology and computer science and

engineering at Michigan State University, categorizes AI into four types, from the kind of AI systems

that exist today to sentient systems, which do not yet exist. His categories are as follows:

-

Type 1: Reactive machines. An example is Deep Blue, the

IBM

chess program that beat

Garry Kasparov in the 1990s. Deep Blue can identify pieces on the chess board and make predictions, but

it has no memory and cannot use past experiences to inform future ones. It analyzes possible moves --

its own and its opponent -- and chooses the most strategic move. Deep Blue and Google's

AlphaGO were

designed for narrow purposes and cannot easily be applied to another situation.

-

Type 2: Limited memory.These AI systems can use past experiences to inform

future

decisions. Some of the decision-making functions in self-driving cars are designed this way.

Observations inform actions happening in the not-so-distant future, such as a car changing lanes. These

observations are not stored permanently.

- Type 3: Theory of mind.

This psychology term refers to the understanding that others

have their own beliefs, desires and intentions that impact the decisions they make. This kind of AI does

not yet exist.

Type 4: Self-awareness.In this category, AI systems have a sense of self,

have

consciousness. Machines with self-awareness understand their current state and can use the information

to infer what others are feeling. This type of AI does not yet exist .

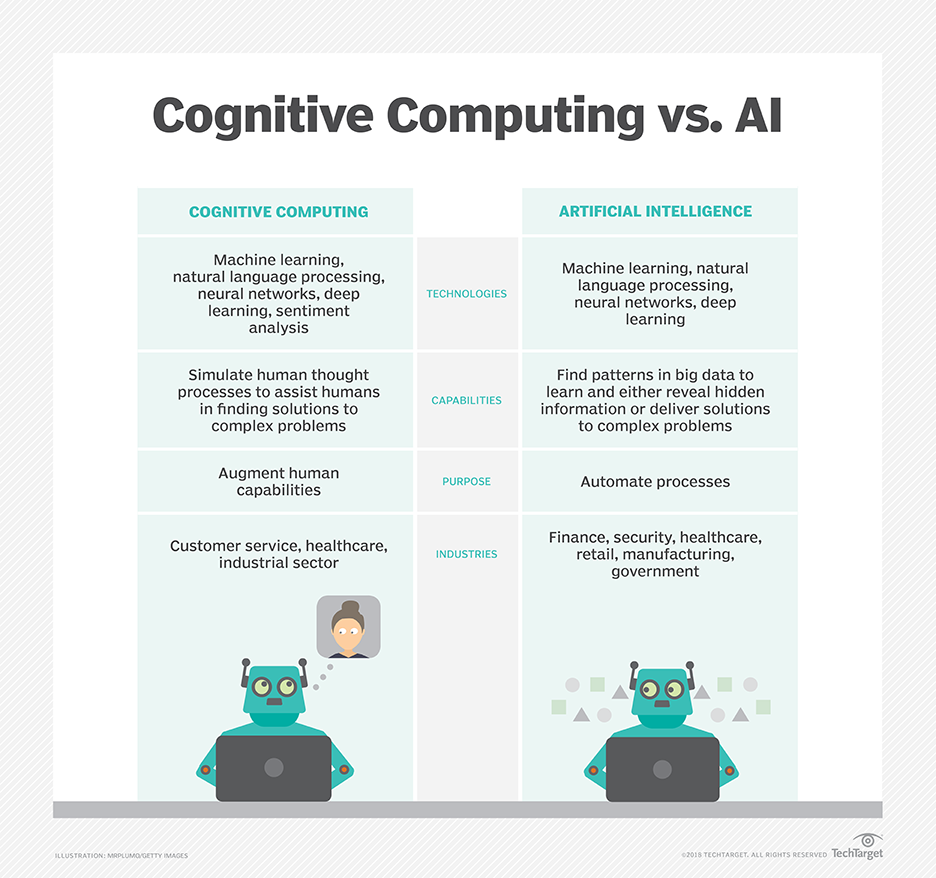

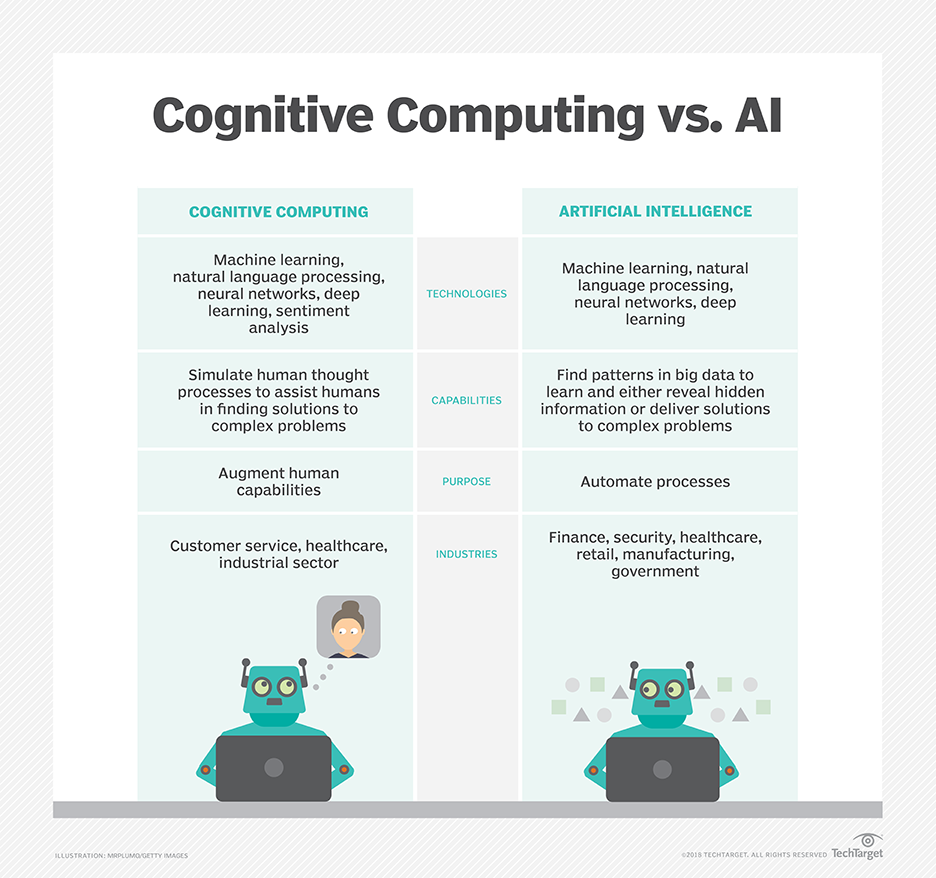

what is the difference between AI and congnitive computing ?

what is the difference between AI and congnitive computing ?

Example of AI technology

AI is incorporated into a variety of different types of technology. Here are seven examples.

-

Automation : What makes a system or process function automatically. For

example,(RPA) can be programmed to perform high-volume, repeatable tasks that humans

normally performed. RPA is different from IT automation in that it can adapt to changing circumstances.

-

Machine learning: The science of getting a computer to act without

programming . Deep

learning

is a subset of machine learning that, in very simple terms, can be thought of as the automation of

predictive analytics. There are three types of machine learning algorithms:

-

supervised learning: Data sets are labeled so that patterns can

be detected and used to label new data sets

-

Unsupervised learning:

Data sets aren't labeled and are sorted according to similarities or

differences

-

Reinforcement learning:

Data sets aren't labeled but, after performing an action or several actions, the AI

system is given feedback

-

Machine vision: The science of allowing computers to see. This technology

captures and

analyzes visual information using a camera, analog-to-digital conversion and digital signal processing.

It is often compared to human eyesight, but machine vision isn't bound by biology and can be programmed

to see through walls, for example. It is used in a range of applications from signature identification

to medical image analysis. Computer vision, which is focused on machine-based image processing, is often

conflated with machine vision.

-

Natural language processing (NLP): The processing of human -- and not

computer --

language by a computer program. One of the older and best known examples of NLP is spam detection, which

looks at the subject line and the text of an email and decides if it's junk. Current approaches to NLP

are based on machine learning. NLP tasks include text translation, sentiment analysis and speech

recognition.

-

Self-driving cars: These use a combination of computer vision, image

recognition and

deep learning to build automated skill at piloting a vehicle while staying in a given lane and avoiding

unexpected obstructions, such as pedestrians.

WHY RESEARCH AI SAFETY?

In the near term, the goal of keeping AI’s impact on society beneficial motivates research in many areas,

from economics and law to technical topics such as verification, validity, security and control. Whereas it

may be little more than a minor nuisance if your laptop crashes or gets hacked, it becomes all the more

important that an AI system does what you want it to do if it controls your car, your airplane, your

pacemaker, your automated trading system or your power grid. Another short-term challenge is preventing a

devastating arms race in lethal autonomous weapons.

In the long term, an important question is what will happen if the quest for strong AI succeeds and an AI

system becomes better than humans at all cognitive tasks. As pointed out by I.J. Good in 1965, designing

smarter AI systems is itself a cognitive task. Such a system could potentially undergo recursive

self-improvement, triggering an intelligence explosion leaving human intellect far behind. By inventing

revolutionary new technologies, such a superintelligence might help us eradicate war, disease, and poverty,

and so the creation of strong AI might be the biggest event in human history. Some experts have expressed

concern, though, that it might also be the last, unless we learn to align the goals of the AI with ours

before it becomes superintelligent.

There are some who question whether strong AI will ever be achieved, and others who insist that the creation

of superintelligent AI is guaranteed to be beneficial. At FLI we recognize both of these possibilities, but

also recognize the potential for an artificial intelligence system to intentionally or unintentionally cause

great harm. We believe research today will help us better prepare for and prevent such potentially negative

consequences in the future, thus enjoying the benefits of AI while avoiding pitfalls.

HOW CAN AI BE DANGEROUS?

Most researchers agree that a superintelligent AI is unlikely to exhibit human emotions like love or hate,

and that there is no reason to expect AI to become intentionally benevolent or malevolent. Instead, when

considering how AI might become a risk, experts think two scenarios most likely:

-

The AI is programmed to do something devastating: Autonomous weapons are

artificial

intelligence systems that are programmed to kill. In the hands of the wrong person, these weapons could

easily cause mass casualties. Moreover, an AI arms race could inadvertently lead to an AI war that also

results in mass casualties. To avoid being thwarted by the enemy, these weapons would be designed to be

extremely difficult to simply “turn off,” so humans could plausibly lose control of such a situation. This

risk is one that’s present even with narrow AI, but grows as levels of AI intelligence and autonomy

increase.

-

The AI is programmed to do something beneficial, but it develops a destructive method for achieving

its

goal:

This can happen whenever we fail to fully align the AI’s goals with ours, which is

strikingly

difficult. If you ask an obedient intelligent car to take you to the airport as fast as possible, it might

get you there chased by helicopters and covered in vomit, doing not what you wanted but literally what you

asked for. If a superintelligent system is tasked with a ambitious geoengineering project, it might wreak

havoc with our ecosystem as a side effect, and view human attempts to stop it as a threat to be met.

As these examples illustrate, the concern about advanced AI isn’t malevolence but competence. A

super-intelligent AI will be extremely good at accomplishing its goals, and if those goals aren’t aligned with

ours, we have a problem. You’re probably not an evil ant-hater who steps on ants out of malice, but if you’re in

charge of a hydroelectric green energy project and there’s an anthill in the region to be flooded, too bad for

the ants. A key goal of AI safety research is to never place humanity in the position of those ants.

WHY THE RECENT INTEREST IN AI SAFETY

Stephen Hawking, Elon Musk, Steve Wozniak, Bill Gates, and many other big names in science and

technology have recently expressed concern in the media and via open letters about the risks posed by

AI, joined by many leading AI researchers. Why is the subject suddenly in the headlines?

The idea that the quest for strong AI would ultimately succeed was long thought of as science fiction,

centuries or more away. However, thanks to recent breakthroughs, many AI milestones, which experts

viewed as decades away merely five years ago, have now been reached, making many experts take seriously

the possibility of superintelligence in our lifetime. While some experts still guess that human-level AI

is centuries away, most AI researches at the 2015 Puerto Rico Conference guessed that it would happen

before 2060. Since it may take decades to complete the required safety research, it is prudent to start

it now.

Because AI has the potential to become more intelligent than any human, we have no surefire way of

predicting how it will behave. We can’t use past technological developments as much of a basis because

we’ve never created anything that has the ability to, wittingly or unwittingly, outsmart us. The best

example of what we could face may be our own evolution. People now control the planet, not because we’re

the strongest, fastest or biggest, but because we’re the smartest. If we’re no longer the smartest, are

we assured to remain in control?

FLI’s position is that our civilization will flourish as long as we win the race between the growing

power of technology and the wisdom with which we manage it. In the case of AI technology, FLI’s position

is that the best way to win that race is not to impede the former, but to accelerate the latter, by

supporting AI safety research.

THE TOP MYTHS ABOUT ADVANCED AI

A captivating conversation is taking place about the future of artificial intelligence and what it

will/should mean for humanity. There are fascinating controversies where the world’s leading experts

disagree, such as: AI’s future impact on the job market; if/when human-level AI will be developed;

whether this will lead to an intelligence explosion; and whether this is something we should welcome or

fear. But there are also many examples of of boring pseudo-controversies caused by people

misunderstanding and talking past each other. To help ourselves focus on the interesting controversies

and open questions — and not on the misunderstandings — let’s clear up some of the most common myths.

[Image source Internet]

[Image source Internet]

TIMELINE MYTHS

The first myth regards the timeline: how long will it take until machines greatly supersede

human-level

intelligence? A common misconception is that we know the answer with great certainty.

One popular myth is that we know we’ll get superhuman AI this century. In fact, history is full of

technological over-hyping. Where are those fusion power plants and flying cars we were promised we’d

have by now? AI has also been repeatedly over-hyped in the past, even by some of the founders of the

field. For example, John McCarthy (who coined the term “artificial intelligence”), Marvin Minsky,

Nathaniel Rochester and Claude Shannon wrote this overly optimistic forecast about what could be

accomplished during two months with stone-age computers: “We propose that a 2 month, 10 man study of

artificial intelligence be carried out during the summer of 1956 at Dartmouth College […] An attempt

will be made to find how to make machines use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds

of

problems now reserved for humans, and improve themselves. We think that a significant advance can be

made in one or more of these problems if a carefully selected group of scientists work on it

together

for a summer.”

On the other hand, a popular counter-myth is that we know we won’t get superhuman AI this century.

Researchers have made a wide range of estimates for how far we are from superhuman AI, but we

certainly

can’t say with great confidence that the probability is zero this century, given the dismal track

record

of such techno-skeptic predictions. For example, Ernest Rutherford, arguably the greatest nuclear

physicist of his time, said in 1933 — less than 24 hours before Szilard’s invention of the nuclear

chain

reaction — that nuclear energy was “moonshine.” And Astronomer Royal Richard Woolley called

interplanetary travel “utter bilge” in 1956. The most extreme form of this myth is that superhuman

AI

will never arrive because it’s physically impossible. However, physicists know that a brain consists

of

quarks and electrons arranged to act as a powerful computer, and that there’s no law of physics

preventing us from building even more intelligent quark blobs.

There have been a number of surveys asking AI researchers how many years from now they think we’ll

have

human-level AI with at least 50% probability. All these surveys have the same conclusion: the

world’s

leading experts disagree, so we simply don’t know. For example, in such a poll of the AI researchers

at

the 2015 Puerto Rico AI conference, the average (median) answer was by year 2045, but some

researchers

guessed hundreds of years or more.

There’s also a related myth that people who worry about AI think it’s only a few years away. In

fact,

most people on record worrying about superhuman AI guess it’s still at least decades away. But they

argue that as long as we’re not 100% sure that it won’t happen this century, it’s smart to start

safety

research now to prepare for the eventuality. Many of the safety problems associated with human-level

AI

are so hard that they may take decades to solve. So it’s prudent to start researching them now

rather

than the night before some programmers drinking Red Bull decide to switch one on.

CONTROVERSY MYTHS

Another common misconception is that the only people harboring concerns about AI and advocating AI

safety research are luddites who don’t know much about AI. When Stuart Russell, author of the standard

AI textbook, mentioned this during his Puerto Rico talk, the audience laughed loudly. A related

misconception is that supporting AI safety research is hugely controversial. In fact, to support a

modest investment in AI safety research, people don’t need to be convinced that risks are high, merely

non-negligible — just as a modest investment in home insurance is justified by a non-negligible

probability of the home burning down.

It may be that media have made the AI safety debate seem more controversial than it really is. After

all, fear sells, and articles using out-of-context quotes to proclaim imminent doom can generate more

clicks than nuanced and balanced ones. As a result, two people who only know about each other’s

positions from media quotes are likely to think they disagree more than they really do. For example, a

techno-skeptic who only read about Bill Gates’s position in a British tabloid may mistakenly think Gates

believes superintelligence to be imminent. Similarly, someone in the beneficial-AI movement who knows

nothing about Andrew Ng’s position except his quote about overpopulation on Mars may mistakenly think he

doesn’t care about AI safety, whereas in fact, he does. The crux is simply that because Ng’s timeline

estimates are longer, he naturally tends to prioritize short-term AI challenges over long-term ones.

MYTHS ABOUT THE RISKS OF SUPERHUMAN AI

Many AI researchers roll their eyes when seeing this headline: “Stephen Hawking warns that rise of

robots may be disastrous for mankind.” And as many have lost count of how many similar articles

they’ve

seen. Typically, these articles are accompanied by an evil-looking robot carrying a weapon, and they

suggest we should worry about robots rising up and killing us because they’ve become conscious and/or

evil. On a lighter note, such articles are actually rather impressive, because they succinctly summarize

the scenario that AI researchers don’t worry about. That scenario combines as many as three separate

misconceptions: concern about consciousness, evil, and robots.

If you drive down the road, you have a subjective experience of colors, sounds, etc. But does a

self-driving car have a subjective experience? Does it feel like anything at all to be a self-driving

car? Although this mystery of consciousness is interesting in its own right, it’s irrelevant to AI risk.

If you get struck by a driverless car, it makes no difference to you whether it subjectively feels

conscious. In the same way, what will affect us humans is what superintelligent AI does, not how it

subjectively feels.

The fear of machines turning evil is another red herring. The real worry isn’t malevolence, but

competence. A superintelligent AI is by definition very good at attaining its goals, whatever they may

be, so we need to ensure that its goals are aligned with ours. Humans don’t generally hate ants, but

we’re more intelligent than they are – so if we want to build a hydroelectric dam and there’s an anthill

there, too bad for the ants. The beneficial-AI movement wants to avoid placing humanity in the position

of those ants.

The consciousness misconception is related to the myth that machines can’t have goals. Machines can

obviously have goals in the narrow sense of exhibiting goal-oriented behavior: the behavior of a

heat-seeking missile is most economically explained as a goal to hit a target. If you feel threatened by

a machine whose goals are misaligned with yours, then it is precisely its goals in this narrow sense

that troubles you, not whether the machine is conscious and experiences a sense of purpose. If that

heat-seeking missile werechasing you, you probably wouldn’t exclaim: “I’m not worried, because

machines

can’t have goals!”

I sympathize with Rodney Brooks and other robotics pioneers who feel unfairly demonized by

scaremongering tabloids, because some journalists seem obsessively fixated on robots and adorn many of

their articles with evil-looking metal monsters with red shiny eyes. In fact, the main concern of the

beneficial-AI movement isn’t with robots but with intelligence itself: specifically, intelligence whose

goals are misaligned with ours. To cause us trouble, such misaligned superhuman intelligence needs no

robotic body, merely an internet connection – this may enable outsmarting financial markets,

out-inventing human researchers, out-manipulating human leaders, and developing weapons we cannot even

understand. Even if building robots were physically impossible, a super-intelligent and super-wealthy AI

could easily pay or manipulate many humans to unwittingly do its bidding.

The robot misconception is related to the myth that machines can’t control humans. Intelligence enables

control: humans control tigers not because we are stronger, but because we are smarter. This means that

if we cede our position as smartest on our planet, it’s possible that we might also cede control.

How Artificial Intelligence Is Being Used

"Every industry has a high demand for AI capabilities – especially question answering systems

that

can be used for legal assistance, patent searches, risk notification and medical research. Other uses of

AI

include:"

Health Care

AI applications can provide personalized medicine and X-ray readings. Personal health care

assistants can act as life coaches, reminding you to take your pills, exercise or eat healthier.

Retail

AI provides virtual shopping capabilities that offer personalized recommendations and discuss

purchase options with the consumer. Stock management and site layout technologies will also be

improved with AI.

Manufacturing

AI can analyze factory IoT data as it streams from connected equipment to forecast expected load

and demand using recurrent networks, a specific type of deep learning network used with sequence

data.

Banking

Artificial Intelligence enhances the speed, precision and effectiveness of human efforts. In

financial institutions, AI techniques can be used to identify which transactions are likely to

be fraudulent, adopt fast and accurate credit scoring, as well as automate manually intense data

management tasks.

Working together with AI

Artificial intelligence is not here to replace us. It augments our abilities and makes us better

at what we do. Because AI algorithms learn differently than humans, they look at things

differently. They can see relationships and patterns that escape us. This human, AI partnership

offers many opportunities. It can:

- Bring analytics

to industries and domains where it’s currently underutilized.

- Improve the performance of existing analytic technologies, like computer vision and time

series analysis.

- Break down economic barriers, including language and translation barriers.

- Augment existing abilities and make us better at what we do.

- Give us better vision, better understanding, better memory and much more.

<

></>

What are the challenges of using artificial intelligence?

Artificial intelligence is going to change every industry, but we have to understand its limits.

The principle limitation of AI is that it learns from the data. There is no other way in which knowledge can

be incorporated. That means any inaccuracies in the data will be reflected in the results. And any

additional layers of prediction or analysis have to be added separately.

Today’s AI systems are trained to do a clearly defined task. The system that plays poker cannot play

solitaire or chess. The system that detects fraud cannot drive a car or give you legal advice. In fact, an

AI system that detects health care fraud cannot accurately detect tax fraud or warranty claims fraud.

In other words, these systems are very, very specialized. They are focused on a single task and are far from

behaving like humans.

Likewise, self-learning systems are not autonomous systems. The imagined AI technologies that you see in

movies and TV are still science fiction. But computers that can probe complex data to learn and perfect

specific tasks are becoming quite common.

Comments

Post a Comment